“Driving While Black” and Racial Fear: An Interview with Pastor Jimi Calhoun

- evangelicals4justice

- Jul, 02, 2014

- Uncategorized

- No Comments

Last week, three trials involving African American men shot and killed by police officers concluded with no guilty verdicts. Each of the incidents began with traffic stops and the shootings were caught on video. The outcry of anger and fear in the African American community is high. Do we who are white ever ask ourselves what it would feel like to be “driving while black”?

I reached out to Jimi Calhoun (JC), an African American, a pastor, community activist, author and musician based in Austin, Texas, to ask for his perspective and recommendations on how to approach these tragedies and widespread racial fear in hopes of creating understanding, trust, and safety in our communities. Here is our interview:

PLM: Pastor Calhoun, a lot of people will say that African Americans simply need to speak calmly and respectfully as well as comply when police officers stop them when driving. Then there will be no problems. How would you respond?

JC: This is tough to answer in a manner that will address the “common sense” implication inherent in the statement itself. People who hold to the “better behavior, better outcome” view more than likely reach that conclusion based on their own personal experience, or those experiences shared by others within their community. I am confident that if I were to share the many times I have behaved calmly and respectfully only to be handcuffed while being questioned or receiving a driving citation, it would zoom right by many individuals and not have much effect. Would the fact that I have been beaten with a nightstick while handcuffed because a bank employee wrongly identified me as a robbery suspect paint a clearer picture of what the problem is? Consider this: I have been handcuffed in my own home after I called the police to report a crime on my property. In this instance they said, “It was for their protection until they were sure who I was.” Should not common sense have said to the officers that I was probably the person who phoned, being that I opened the door for them? Anecdotal evidence that contradicts, or that does not comport with, the presuppositions of people who hold the “if they had only behaved view” is typically dismissed as simply an anomaly. This is because the assumption that police officers treat every person the same way is so ingrained in the suburban mindset that it is difficult to imagine the possibility that equal treatment could be more of an ideal than a reality.

PLM: Sometimes one hears the expression, “Driving While Black.” What does that mean?

JC: It means many things, but for me it is ultimately rooted in one word, “Belonging.” One of the first waves of justification for the killing of Trayvon Martin while walking in a Florida suburb was that “he didn’t belong there.” That meant that the person who ultimately killed him was absolutely right to note his presence and follow him in order to see “what he was up to.” Perhaps it is due to the segregation laws of the past, or today’s practice of self-segregating, but it is often taken for granted by many whites that people of color belong in certain places, and it is abnormal for them to be where they don’t belong! That perspective can have an effect on every area of African American life way beyond police interactions.

Allow me to share a non-police related story to help you understand my point. I attended a pastor’s conference in rural Texas when the Martin case was news. My hotel was situated a few yards off a major highway. Down the road about one-half mile was a traffic light, and had I turned right there, I would have soon been in a residential community. I like to run in the morning for exercise. I made the decision that it was safer for me to run along the highway— dodging the semis, distracted drivers and other hazards posed by early morning rush hour traffic—than run in a dimly lit, and presumably heavily armed neighborhood, in a section of Texas where I “didn’t belong!”

PLM: It is important to note that in the three trials mentioned above the police officers were of diverse ethnicity. Some might argue that such diversity goes to show the shootings were not racially motivated. What would you say in response?

JC: The first thing I learned about ministering cross-culturally was to never presume you can know the motivation of another human being, and never act on your presumption by impugning the motivation of another. That said, allow me to share a story that illustrates the difficulty in assigning “intent” either way.

At present, I spend a considerable amount of time with people who are living with physical and intellectual disabilities. This racially diverse population is viewed as being “one group” by people both outside and inside the group. We refer to them as “the disabled,” and not the black disabled or the native disabled. In the non-disabled population, race is everything. We have black church, white church, black neighborhood, white neighborhood, etc. In the broader culture, we accept these societal arrangements as normal and natural. Yet I am absolutely sure my disabled friends would view our social arrangements quite differently, and their lifestyles are living proof that they are right.

I look at the police as being more like the disabled community—one group of diverse parts acting in unity. This comparison is intended to convey that a person is a police officer first before they are black or white, just like a person is disabled before they are black or white. If my theory is even close to being accurate, then I would imagine the race of the shooter, or the victim, would not be a major factor in the tragedy. What matters most is alignment within the community. Whoever is seen most as a support or as a threat to the group is seen in the same way by the individual member, whether a disabled person or a police officer.

PLM: Here I call to mind “Black Lives Matter.” While the movement is very controversial to many readers, at its heart, the statement is about valuing African American lives, not about degrading others. From slavery to Jim Crow and lynchings to the percentage of mass incarcerations as well as police shootings today, along with other structural problems including lack of opportunities, African American men may be viewed as endangered. I share this concern. How would you assess this situation, including the racial fear?

JC: Right now, I have a very popular and successful Christian book open that contains the term “blacklisting.” I was taken aback when I first read it and had to go back and read the context several times before being offended. The immediate context determined that in the book “blacklisting” means “out-casted” or rejected. When I read your question, I immediately thought back to my feeling when first pondering the term in the book. Then I realized that if I simply replaced “blacklisting” with “out-casted,” it perfectly described how African American males are positioned in our culture—often summarily rejected. Why and how did the black male come to be so feared? Here’s one way.

A few years ago, my ministry partner named Robert sent me a link that featured white elementary school kids being exposed to a series of images and then pressing a button to indicate a positive or negative feeling about each one. These kids were given access to these images in rapid succession in order to compile a list of unfiltered responses to images of people, dogs, cars, etc. As you may have anticipated, even at that early age, the kids overwhelmingly preferred the lighter object to the darker. If you are reading this and you are white, I am going to venture a guess that you are saying to yourself, “That is natural and after all they are just kids anyway so what does that prove?”

My response: cultures are cultivated, meaning they exist as a result of human effort of some sort. The preference for the “lighter” is not innate. I lived in The Caribbean for eight years. During that time, I lost all sense of the American preference for the lighter. All of the newscasters were darker skinned. People in prominent positions were darker skinned. When I would come back to the States and turn on a television here, it was actually the blonde-haired newscasters who seemed odd to me. My point is that our tastes and preferences are definitely a result of external influence, and if we realize that fact, we can begin to unravel one of the threads of racism—prejudice.

PLM: Some will remark that such discussions only alienate the police and devalue their lives. How would you respond?

JC: I believe there is no reason to demonize the police, and it is counterproductive to paint them being a monolith. To steer people away from that type of thinking, I often use a hypothetical scenario where a white police officer is on trial for shooting an unarmed African American youth. I portray the officer as a bright, outgoing and gregarious individual who is a deacon at his church, a coach on his daughter’s soccer team, and loved by everyone in the subdivision where he lives. My question at the end of it is, “Who is this guy?” I do this to humanize the officer in order to take the focus off of him. The picture I just painted is of a nice guy that most would want to have as a neighbor. However, for some reason, one aspect of his character or personality and behavior has torn apart the lives of a family regardless of the justifications presented at the trial. I would ask us all to remember that alienation is easy, reconciliation is hard, but to be reconciled with each other is the desire of the one who matters most.

PLM: Regardless of the results in these cases, what can be done in our communities, such as community policing, to alter the tragic script that is playing out over and over again across this nation?

JC: The first thing I would suggest to do would be to rethink what the role of the police should be in our society. When I was a kid, one descriptor for a police officer was a public servant. In fact, the slogan on the LAPD’s vehicles was “To protect and serve.” This descriptor indicates the job of an officer was to serve the public. Their role was viewed as reactive. In fact, the job consisted of meeting the needs of the community even at the expense of their own lives if necessary. Later it became fashionable to refer to the police as law enforcement, implying that the job was about making sure codes were not violated, and citing or arresting those who violated them. Again, reactive. Today we are comfortable referring to the police as “the authorities,” or peace officers. Many view those names to imply an inherent proactive rather than reactive element to the job, such as preventing people from disrupting the peace. The end result of this type of thinking is that some no longer see the job of a police officer as being a servant, or as a person assigned to insure laws that are obeyed, but as ‘behavior monitors’ for an entire city. It then follows that police should have the authority to drive around a community and engage possible or probable offenders as a preventative measure.

I realize that many reading this might be a little skeptical about my contention that policing may have morphed from a service and response oriented profession to one that is somewhat authoritarian in nature. I would ask that you set aside thinking about the police actions that are the subject of this present conversation and look at the airline industry. Pre-9/11 the entire industry was oriented toward customer satisfaction. Everyone you encountered was polite and helpful. The ability to travel great distances in a short time was seen as a privilege and a luxury. From purchasing the ticket to landing at a destination, it was an enjoyable experience to most. Can the same be said about today’s interaction with the airline industry? I doubt it! What happened? Flight attendants were given federal authority to control the cabin and they can have a passenger removed and arrested at any time they see fit. TSA agents can even prevent you ever using the ticket you purchased if you do no comply with their orders. The shift in the basic understanding about what the job is, coupled with the introduction of power, has altered the relationship between the parties involved, and those type of changes are not always for the good. It was true for the airlines and may just be true about the police.

PLM: Please tell us about your work, and what you are doing in your context to make a difference.

JC: I have a couple of books started that I am very excited about. One is a novel and the other is on ethics. Each of the books addresses justice issues in various ways. We will be formally re-launching the church I pastor “Bridging Austin” in September. Our mission is to be a church community that truly welcomes those living on the margins of the mainstream culture. We are committed to forming a community of diverse people that accepts “the other” as they are, and that’s without a hidden agenda to convert them to who we think they should be. It is true that what I just described is a very tough calling but we’re up for the challenge. We’ve been doing some really cool things with music in the disabled community, and now we’ll go back to where we began by reemphasizing racial reconciliation, too. So this year, I’ll have a church re-launched, hopefully one of the two books published, as well as an album re-released on a British label.

PLM: Do you have any closing reflections?

JC: The cry for justice from people of color that has continued to reverberate for generations is partly the result of an unwillingness of Christian people to face injustice head on. I do not believe the church is heartless or oblivious to the suffering of others—it just typically views injustice forensically or politically. Many Christian people believe that justice must be won in a court of law or come through governmental legislation. Viewing it as a spiritual problem is foreign to them. Court cases won, and legislation passed, rarely change the perspectives of the players involved because they only find new and creative means of achieving their goals. The church must move beyond apathy about, and detachment from, the problems that marginalized people face every day of their lives. For that to happen, the church must return to being in the spirituality business and let the entertainer entertain, the counselor provide the therapy, and the motivational speaker provide the weekly pep talk. The prophet Isaiah lays out one path to healing divisions that the church would do well to remember: “Do right, seek justice, and defend the oppressed.” Those words are more than good advice to me, they are my marching orders, and pursuing those three principles is where you can find me 24/7 should you desire to join me. Bridging Austin can only be found on Facebook at this time, but our website will soon be operational.

– Originally in Patheos

Follow us on Twitter: @Evang4Justice

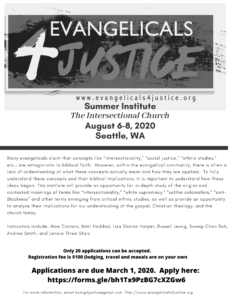

Invalid or expired token.Summer Institute

Recent Posts

- Evangelical Perspectives on Israel and Palestine – by Rob Dalrymple

- Indigenous Peoples and Christian Nationalism by Lenore Three Stars

- Recognizing Nationalism by Andrew Cheung

- Ukraine: “Wars and rumors of wars”: a sign of the times, or a sign of all times? A Christian response by Rob Dalrymple

- E4J Annual Zoom Conference: From Conflict to Community, Feb 11-12, 2022